“This is the first time meditation training has been shown to affect emotional processing in the brain outside of a meditative state,” said Gaelle Desbordes, Ph.D., a research fellow at the Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital and at the Boston University Center for Computational Neuroscience and Neural Technology.During meditation, activity in the amygdala, a part of the brain that processes emotional reactivity, decreased. The participants retained the ability to focus their attention and reduce emotional reactivity over an eight-week period.

“Overall, these results are consistent with the overarching hypothesis that meditation may result in enduring, beneficial changes in brain function, especially in the area of emotional processing.”

Meditation practice isn't about trying to throw ourselves away and become something better. It's about befriending who we already are. - Pema Chodron ... Meditation.Wednesdays.7:30pm.SamadhiYogaStudio.Manchester CT

Monday, June 24, 2013

The after-effects of meditation

New research says meditation helps people process emotions -- even when they're not actively meditating.

Monday, June 17, 2013

Meditation: It's like a nap ... only better

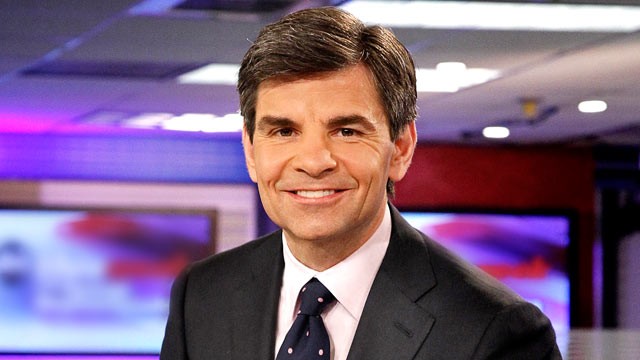

George Stephanopoulos, host of Good Morning America, started meditating after hearing about the scientific benefits. He's been doing it every day for a couple of years now. Now he calls it a lifesaver.

"It's the equivalent of a couple hours more sleep," he told Arianna Huffington during the Third Metric women's conference panel. "I feel more space in my life even when it's not there."

Watch the video here

It's easier to get up at 2:30, he says, because he's getting up to relax. And during the day: "It's easier to tap into that quiet ... especially during big breaking news situations, it's easier to find that space."

"It's the equivalent of a couple hours more sleep," he told Arianna Huffington during the Third Metric women's conference panel. "I feel more space in my life even when it's not there."

Watch the video here

It's easier to get up at 2:30, he says, because he's getting up to relax. And during the day: "It's easier to tap into that quiet ... especially during big breaking news situations, it's easier to find that space."

Wednesday, June 12, 2013

Meditation took him from Death Row back to life

Damian Echols spent 18 years in prison for murders he didn't commit and was freed nearly two

years ago. He lived on Death Row, and he suffered physically and mentally, he says. To cope with that, he learned eastern methods of working with the body, such as chi gong, and the mind, ordaining in the Rinzai Zen tradition. By the time he left prison, he was meditating for five to seven hours a day.

Now he teaches meditation.

In a blog post at Salon, Echols says:

years ago. He lived on Death Row, and he suffered physically and mentally, he says. To cope with that, he learned eastern methods of working with the body, such as chi gong, and the mind, ordaining in the Rinzai Zen tradition. By the time he left prison, he was meditating for five to seven hours a day.

Now he teaches meditation.

In a blog post at Salon, Echols says:

I didn’t turn to meditation and energy work out of hope that I’d find nirvana in some distant future. I turned to it because I needed help dealing with the pain and suffering of everyday existence in a living hell. Those techniques I had to learn out of necessity to survive and deal with pain are the same techniques I now teach to other people. It’s my passion in life. It’s what I love doing.

When I teach these methods of meditation, I avoid the pitfalls of religious dogma. Instead, I focus on the science. I explain how our minds communicate with our bodies through chemicals called neuropeptides, and we can program these neuropeptides to speed up the healing process in our body with simple visualization and breathing exercises. I want to make it accessible to people of all belief systems, not only Buddhists.I've never been to prison, and I don't talk about neuropeptides. But I practice meditation and teach meditation because I know it can bring liberation from suffering -- bit by bit, we raise our baseline happiness level. If it works for an innocent man on Death Row, how much more can it do for you?

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

Why not meditate?

Most of my posts extoll the virtues of meditation. Maybe I'm taking the wrong approach.

Beth Teitel writes in The Boston Globe that "the studies showing the benefits of mindfulness and meditation are so relentless that I need to retreat to a monastery just to get away from the news. Nothing’s more stressful than hearing about the advantages of something you’re not doing."

So if you've heard about the famous meditators -- from Congressional representatives to athletes to celebrities -- and you're still not moved to start practicing, you're not alone. But you're starting to have less company. In 2007, according to the National Institutes of Health, 9.4 percent of American adults had meditated with the last 12 months, up from 7.6 percent in 2002. I'd guess the 9.4 percent will go up when the 2012 numbers are in.

Meditation has all kinds of benefits -- ones that you'll notice, more subtle ones that researchers have found in MRIs, ones that the Buddha promised. But you have to do.

The Globe article offers the following tips on starting a practice from Barry Boyce, editor of Mindful magazine.

1. Go online to get a clearer picture of just what mindfulness meditation is, anyway. Mind the Moment at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care offers a series of short, fun, and accessible videos. A YouTube video called “What Is Mindfulness?” with Jon Kabat-Zinn is also a great place to start.

2. Learn how to do mindfulness practice online: A great resource is www.mindful.org — in particular the section called “Mindfulness: The Basics.”

3. Read a short book such as “Mindfulness for Beginners,” by Kabat-Zinn, or “A Mindful Nation” by congressman Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), an avid meditator.**I really like Real Happiness by Sharon Salzberg, which gives a progressive guide to starting a practice. The website lets you download the first chapter and offers audio for guided meditation.

4. Find a local group and try it with a live instructor. Come to Samadhi -- every week there's a mix of beginners and more experienced meditators, instruction, and time for questions. Everyone's experience is different every time, so however it is, that's just how it is that night.

Beth Teitel writes in The Boston Globe that "the studies showing the benefits of mindfulness and meditation are so relentless that I need to retreat to a monastery just to get away from the news. Nothing’s more stressful than hearing about the advantages of something you’re not doing."

So if you've heard about the famous meditators -- from Congressional representatives to athletes to celebrities -- and you're still not moved to start practicing, you're not alone. But you're starting to have less company. In 2007, according to the National Institutes of Health, 9.4 percent of American adults had meditated with the last 12 months, up from 7.6 percent in 2002. I'd guess the 9.4 percent will go up when the 2012 numbers are in.

Meditation has all kinds of benefits -- ones that you'll notice, more subtle ones that researchers have found in MRIs, ones that the Buddha promised. But you have to do.

The Globe article offers the following tips on starting a practice from Barry Boyce, editor of Mindful magazine.

1. Go online to get a clearer picture of just what mindfulness meditation is, anyway. Mind the Moment at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care offers a series of short, fun, and accessible videos. A YouTube video called “What Is Mindfulness?” with Jon Kabat-Zinn is also a great place to start.

2. Learn how to do mindfulness practice online: A great resource is www.mindful.org — in particular the section called “Mindfulness: The Basics.”

3. Read a short book such as “Mindfulness for Beginners,” by Kabat-Zinn, or “A Mindful Nation” by congressman Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), an avid meditator.**I really like Real Happiness by Sharon Salzberg, which gives a progressive guide to starting a practice. The website lets you download the first chapter and offers audio for guided meditation.

4. Find a local group and try it with a live instructor. Come to Samadhi -- every week there's a mix of beginners and more experienced meditators, instruction, and time for questions. Everyone's experience is different every time, so however it is, that's just how it is that night.

Thursday, June 6, 2013

The good thing about feeling bad

Meditation is about making friends with our whole being and learning to accept what we're tempted to reject, suppress, or avoid because it feels uncomfortable. I know, from personal experience, that's a beneficial thing. Now there's scientific evidence.

Scientific American reports here:

But Pollyana is not the model for mental health. Ignoring or surpressing thoughts we consider bad or negative doesn't make them go away -- researchers found that people who tried to suppress a negative thought before sleep went on to dream about it. t also can lead to substance abuse as a way to avoid them.

The key is to acknowledge the feelings, sit with the discomfort, and learn that -- like happiness -- it comes and goes. That's what we train in doing in meditation. (The article cites a 2012 study that found that a therapy that included mindfulness training helped individuals overcome anxiety disorders. It worked not by minimizing the number of negative feelings but by training patients to accept those feelings.)

Scientific American reports here:

A positive mental attitude does have benefits. Back before MRIs and brain studies, the Buddha listed the benefits of practicing metta meditation to turn the mind toward thoughts of loving-kindness. Anecdotal evidence -- and now scientific research -- confirm this.

Anger and sadness are an important part of life, and new research shows that experiencing and accepting such emotions are vital to our mental health. Attempting to suppress thoughts can backfire and even diminish our sense of contentment. “Acknowledging the complexity of life may be an especially fruitful path to psychological well-being,” says psychologist Jonathan M. Adler of the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering.

But Pollyana is not the model for mental health. Ignoring or surpressing thoughts we consider bad or negative doesn't make them go away -- researchers found that people who tried to suppress a negative thought before sleep went on to dream about it. t also can lead to substance abuse as a way to avoid them.

“Taking the good and the bad together may detoxify the bad experiences, allowing you to make meaning out of them in a way that supports psychological well-being,” the researchers found.That is, of course, counter to our culture's emphasis on happiness, on making everything all good/all the time.

The key is to acknowledge the feelings, sit with the discomfort, and learn that -- like happiness -- it comes and goes. That's what we train in doing in meditation. (The article cites a 2012 study that found that a therapy that included mindfulness training helped individuals overcome anxiety disorders. It worked not by minimizing the number of negative feelings but by training patients to accept those feelings.)

Wednesday, June 5, 2013

Can mindfulness reduce prescription errors?

A British study suggests that mindfulness could help pharmacists avoid making costly and dangerous medication errors.

In over 60 percent of cases, medication errors are associated with one or more

contributory, individual factors including staff being forgetful, stressed, tired or engaged in multiple tasks simultaneously, often alongside being distracted or interrupted. Routinised hospital practice can lead professionals to work in a state of mindlessness, where it is easy to be unaware of how both body and mind are functioning. ...

There is expanding evidence on the effectiveness of mindfulness in the treatment of many mental and physical health problems in the general population, as well as its role in enhancing decision making, empathy, and reducing burnout or fatigue in medical staff. Considering the benefits of mindfulness, the authors suggest that health-care professionals should be encouraged to develop their practice of mindfulness.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)